Ontario’s Environmental Commissioner has slammed the provincial government over its woodland caribou conservation efforts.

In his 2010-2011 environment report, Environmental Commissioner Gord Miller criticized Ontario’s inadequate monitoring of caribou populations and the lack of public engagement on caribou management plans. He noted that public backlash against caribou conservation efforts, especially from the forestry sector, was often led by a lack of information on caribou populations and what conservation efforts mean.

“By failing to keep the public informed of its progress, (the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources) is allowing this public anxiety to fester,” Miller wrote. “Only with a current and clear understanding of caribou population, range and distribution can a rational discussion be had about conserving Ontario’s caribou.”

Miller also noted that caribou conservation may not have the dire effect on forestry that some industry stakeholders have claimed.

“If robust monitoring data were publicly available, the public might be surprised by the limited extent to which conservation measures would actually affect local communities,” the report said.

Woodland caribou were listed as a threatened species under Ontario’s Endangered Species Act in 2007.

Ontario’s Ministry of Natural Resources (MNR) released its Caribou Conservation Plan in 2009. At the time Miller panned the plan as a “reiteration of the very status quo” that has already led to caribou decline across the Far North.

The Caribou Conservation Plan was also rejected by forestry industry groups, who claimed wood supplies would be limited because of broad conservation plans to protect caribou in the boreal forest.

Woodland caribou numbers in Ontario were estimated at 5,000 animals earlier this decade.

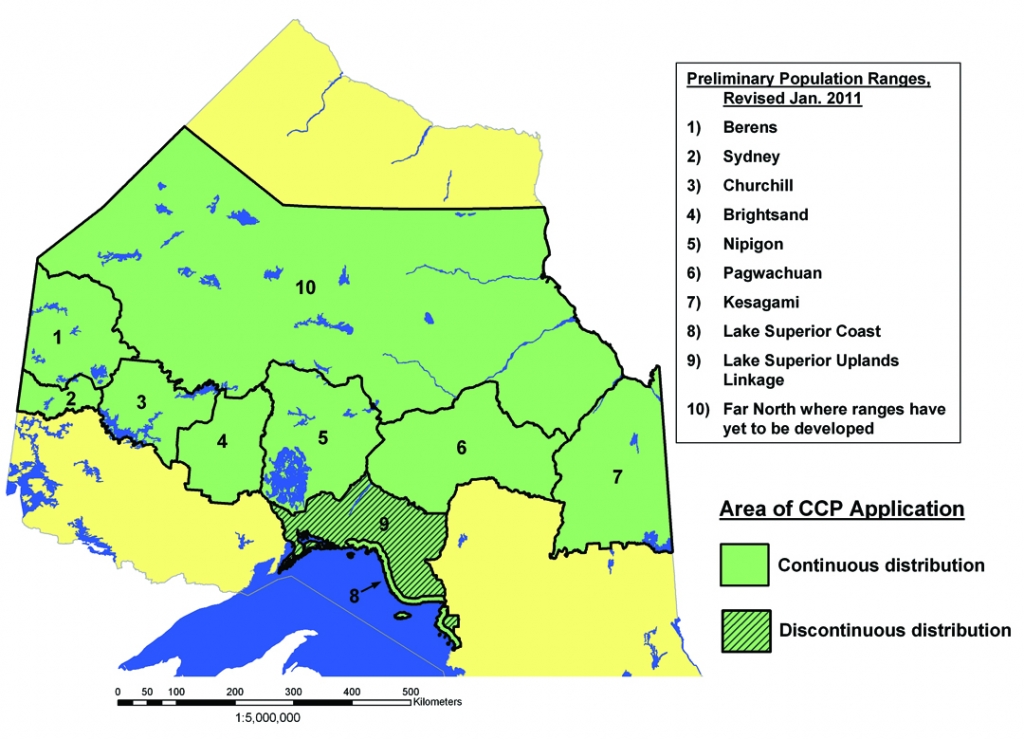

The MNR is in the process of updating those estimates by completing woodland caribou population and habitat studies. The department has finished assessments on two of nine caribou ranges, with plans to study all of the ranges over the next four years. The results of the first two range studies are expected to be released in early 2012.

As a growing number of roads, power line corridors and other developments spread further north in Ontario, a recent study from Alberta may shed some light on the future of Ontario’s woodland caribou.

John Nagy is a PhD candidate from the University of Alberta who has spent most of his working life studying caribou across Alberta, Northwest Territories (NWT) and Nunavut.

He analyzed satellite data from radio collars on boreal forest caribou in both northern Alberta and the NWT.

Nagy’s findings showed that caribou avoid cleared corridors through the forest, whether those are roads, seismic lines or power line corridors. Nagy’s study also showed that predators, especially wolves, use the seismic lines and power lines for travelling and for hunting caribou.

The collared caribou preferred to stay at least 400 metres from the corridors, in the safety of the thick forest.

Comparing populations from northern Alberta, where seismic lines and other disturbances criss-cross the forest, and further north in the more isolated regions of the NWT, Nagy determined that woodland caribou populations with 500 square kilometres of unbroken forest were all stable and healthy.

In contrast, caribou populations without 500 square kilometres of unbroken forest to roam were all in decline.

“The story here is that we need to maintain large patches of unimpacted land if we want boreal caribou to remain as self-sustaining populations,” Nagy said.

When asked about Nagy’s findings, Anna Baggio of the Wildlands League pointed to her organization’s 2009 report on the future of woodland caribou in Ontario.

That document, Caribou range condition in Ontario, found that of the nine regions identified as caribou ranges in northern Ontario, seven were so disturbed by roads, forestry operations and forest fires as to make the future survival of caribou difficult at best.

But Baggio noted that the problems of how to manage caribou populations in Ontario do not relate only to the amount of disturbed land in the regions.

There has also been a complete lack of systematic monitoring of caribou, she said, explaining that the government has failed to do population estimates on the different ranges and failed to determine the numbers of calves per females, a crucial statistic when determining the health of a population.

“The monitoring has simply not been done,” Baggio said.

Michael Gluck, MNR’s manager of caribou conservation, acknowledged that population counts in the past have been only a rough estimate of woodland caribou. But he said the government has started to do the necessary work for effective caribou conservation as part of its caribou management plan.

A big part of that work is the ongoing woodland caribou range assessments, Gluck explained. MNR plans to do range assessments of the nine woodland caribou ranges over the next five years.

Range assessments involve aerial surveys of the range to complete a population count, and collaring 20 females on the range to determine movement patterns as well as birth rates of the animals.

The department is in year two of that initiative and to date the Nipigon range, around Lake Nipigon, and the Kesagami range, along the Quebec-Ontario border near Kirkland Lake, assessments have been completed.

Gluck said the results of those first two assessments will be released to the public early in 2012.

Preliminary results show that both the Nipigon and the Kesagami ranges have over 300 animals, which Gluck said is the number of animals needed to ensure that inbreeding does not cause genetic problems in the herd. The caribou population in the Nipigon range appears to be stable, based on the number of successful births from pregnant cows studied as part of the assessment. In the Kesagami range however, the population appears to be decreasing.

Gluck said both ranges have roughly 35 to 40 per cent disturbance from human activities like development and forest fires. The government believes having 40 to 60 per cent of the range undisturbed is essential for survival of the caribou, so both ranges are close to the threshold for disturbance.

As for the Environmental Commissioner’s criticism that a lack of public information has led to “public anxiety” over caribou management in Ontario, Gluck said that when the first two range assessments are released in 2012 the public will have much more information about the government’s caribou management plans.

He also disputed claims that caribou management effectively means blocking industry from accessing the land.

He said the Caribou Management Plan allows for both caribou survival and resource development.

Gold has arrived.

Gold has arrived. Here in the north of Ontario we see vast streams of gold shimmering across the landscape as autumn is here and the the leaves are turning...

I am the product, evolution of many thousands of years as are you. I grew up on the land in the remote far north of Ontario following in the footsteps of my...