http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eR7pQAVtWrk&feature=youtu.be

Watch this mini-documentary about Dechinta Bush University and hear from people creating a new paradigm for education in the north. Produced by Angela Sterritt, shot by Graham Shishkov and edited by Davis Heslep and Jeremy Emerson.

By Angela Sterritt

TheTyee.ca

[Editor’s note: This is the first is a series of reports on successful youth-focused projects resulting from collaboration between Indigenous communities and philanthropic organizations. Leading Now is itself a collaboration of Journalists for Human Rights, The Tyee Solutions Society, the Wawatay Native Communications Society, and the J. W. McConnell Family Foundation which commissioned this journalism.]

It was late afternoon at Blachford Lake in Akaitcho Territory, Denendeh, the Dene name for the Northwest Territories. Indigenous youth circled around an open fire on rocky terrain and learned about self-determination and the land. They were students gaining knowledge in a unique university, one rooted in the land and life on it. It’s called Dechinta – the bush university.

Dechinta combines theory and academia with land-based cultural activities -- like tanning moose hides -- and Indigenous knowledge. It was mandated to develop an institution of higher learning in the Canadian North.

Erin Freeland Ballantyne, the Territory’s first Rhodes scholar, ultimately started the Bush University in 2008. The self-identified “settler” said Dechinta grew out of the need to provide an alternative to mainstream education in the North.

A fifth generation Caucasian northerner, born and raised on Yellowknives Dene First Nations Territory, 32-year-old Freeland Ballantyne said she was always aware of differences in treatment between Indigenous and non-Indigenous high school students. She remembered taking a Native studies class, and being told that the Yellowknives Dene were extinct (while living amongst many).

Witnessing such a prominent discrepancy between the sophistication of Dene education on the land and how that was discounted in classroom learning, Freeland Ballantyne was inspired early on in life to question her responsibilities, as someone who recognized the conflicted environment around her.

“What is the settler responsibility to Dene land claims and the state’s denial of their rights and title to the land? How do you reconcile that?” she said during an interview at her home in Yellowknife in the summer of 2013. “Are you acquiescing if you are not actively doing something to tear it apart”?

Freeland Ballantyne said that she was taught if you want change, you have to commit your resources.

“Mine were my family, education and white privilege. I realized I have to dedicate myself to make things less destructive and less awful.”

In the north, the petroleum industry was conventionally viewed as the primary means of economic opportunity and sustainability. The Mackenzie Valley Pipeline hearings opened up a new dialogue about other options. Freeland Ballantyne was part of a group that was allowed intervener status at the hearings. It pressed her to think seriously about northern alternatives.

While doing her PHD in 2006, Freeland Ballantyne lived in Fort Good Hope, Northwest Territories, and worked with a group of young Dene women. These students were innovative, intelligent, and creative, but treated as the opposite in high school. Teachers didn’t respect the base of knowledge they carried. Her premise—that students would benefit by shifting the educational paradigm in the north—then crystallized.

In 2008 Freeland Ballantyne wrote a vision document to propose the idea of a northern university. She distributed it to everyone she knew - mentors, leaders, Elders, Ministers of the territorial government, and members of the Yellowknives Dene First Nation. Within a week she had an advisory circle: a mix of big-name academics, Elders and northerners.

Discussions crystallized to proposals, and the advisory circle began to shop the project around to funders in 2008. The result: a $50,000 grant from the Walter and Duncan Gordon Foundation to put on a conference in 2009 that would act as a strategic planning session.

From the conference, the advisory produced a “massive” report. After consulting with Elders from various regions, group member Besha Blondin suggested the name “Dechinta.” It means “Bush” in the Dene language.

With a comprehensive economic and academic strategic plan to demonstrate the feasibility of Dechinta, the Walter and Duncan Gordon Foundation granted another $75,000 in 2009.

With it, Freeland Ballantyne hired Kyla Kakfwi-Scott, the daughter of former NWT Premier Stephen Kakfwi, and current Truth and Reconciliation Commissioner Marie Wilson. Freeland Ballantyne said Kakfwi-Scott’s first year was all about building political relationships—with the Government of Northwest Territories Department of Education, Culture and Employment, for example.

“It was a way to get the project from being a great idea on paper to being a living breathing organism,” Kakfwi-Scott said from her office at the Government of the Northwest Territories.

She said she had not heard of Dechinta before Freeland Ballantyne approached her, but she immediately understood the importance of it, based on her own experience.

“Like every northern student, I had to leave the north for university. And I really struggled when I started working on my degree in Ontario. I remember being really lonely -- it wasn’t cold in October and I needed it to be cold. At a First Nations event they served corn and fry bread, which is fine, but it made me feel even lonelier because they were all great people but I needed my caribou.”

“From my own experience, I really connected with the idea that there needed to be a northern university.”

She said there was a clear gap in higher learning that recognized the significant developments - in particular political developments - that have happened in the North over the last forty years. There was also the need for higher learning opportunities for northerners, particularly ones that would provide youth with skills and knowledge relevant to their lives and communities.

But Kakfwi-Scott was adamant that the lessons and history imparted were important for everyone to learn – not just Indigenous people and not just northerners.

“For the changes to be made over the coming years and for the next generation of leaders to face the challenges they are being asked to rise up and take on, there needs to be a common knowledge base and a good solid working relationship.”

One of the greatest challenges has been the Northwest Territories’ Education Act. The legislation, as it stands, recognizes only Aurora College as a credit granting institution in the Northwest Territories. “The Education Act does not allow Dechinta to be a credit-granting organization. However, Dechinta can continue to grant credits indefinitely through partnerships with other universities,” Kakfwi-Scott said.

She said the organizers’ drive to push ahead and run a pilot program in 2010 demonstrated to potential funders that Dechinta could work, regardless.

In 2010 Dechinta was awarded an estimated $300,000 from the Canadian Northern Development Agency. By the summer of 2010 Dechinta had funding to run an accredited three-week pilot program. A six-week winter/spring program followed in 2011, supported by the Canadian Northern Economic Development Agency. Thirty-eight students and teachers, including a baby and an 87-year old, traveled by skidoo to Dene communities with a temperature of -28 degrees Celsius. They trapped, hunting and engaged with such topics as Indigenous self-determination, communications in media, moosehide tanning, health, and medicines.

Kakfwi-Scott said that pilot was the most important step the organization took.

“We had a small cohort of 6 students who came out of it and said this is, bar none, the most important experience of my life so far, the most transformational thing I have done in my life. And they all spoke publicly about it and continue to do so because they felt other people needed to have that experience.”

Currently, each Dechinta semester is 12 weeks long. In the beginning, students spent the first 5 weeks at home in their own community, reading and preparing assignments. That component has since changed, as a lot of the material is heavy and hard to digest alone. Now students start their reading in groups, on site.

Students and faculty spend the semester engaging in lectures, workshops, daily experiences, fire sessions and out-trips. The majority of instruction takes place outdoors. Entrance is based on interviews by the advisory circle; admission requirements are based on life experience, willingness to learn and dedication.

Students choose up to four University of Alberta degree credit courses, on topics ranging from building sustainable communities amidst climate change to Dene self-determination.

Stephen Ellis is Tides Canada’s first Northern Senior Associate. He is also one of the current directors on the board at Dechinta. He said the land element provides an essential balance to heavier topics such as treaties, the relationship with the Crown, first contact and racism. Said Ellis: “Having that balance with Elders on hand to counsel students is critical.”

“The most important part of this work is really truth and reconciliation,” he said, “as a way to foster a better understanding of Indigenous and non-Indigenous people in Canada, and to ensure everyone has a voice and understands the role of treaty people.”

In the winter of 2011, the newly married British Royal couple Will and Kate announced they were coming to Yellowknife. Dechinta wrote a very formal letter to them and found they were on the short list. This inspired a conversation about ethics, according to Freeland Ballantyne.

“How do we welcome them in our space? This is ultimately a conversation between the Crown and the grandchildren of people you signed a treaty with that you have not honored. So what was our responsibility?”

While the visit didn’t achieve what Freeland Ballantyne called naïve goals, it did, as some have speculated, raise awareness about Dechinta.

Ellen Bielawski, a northern Alaskan scholar who had lived in Lutsel’ke, Northwest Territories, helped facilitate getting Dechinta accredited by the University of Alberta. In the spring of 2013, Dechinta’s directors signed an memorandum of understanding with the University of Alberta’s new Dean of Native Studies and can now run a minor program. They have a similar relationship with McGill and are in discussions with the University of British Columbia.

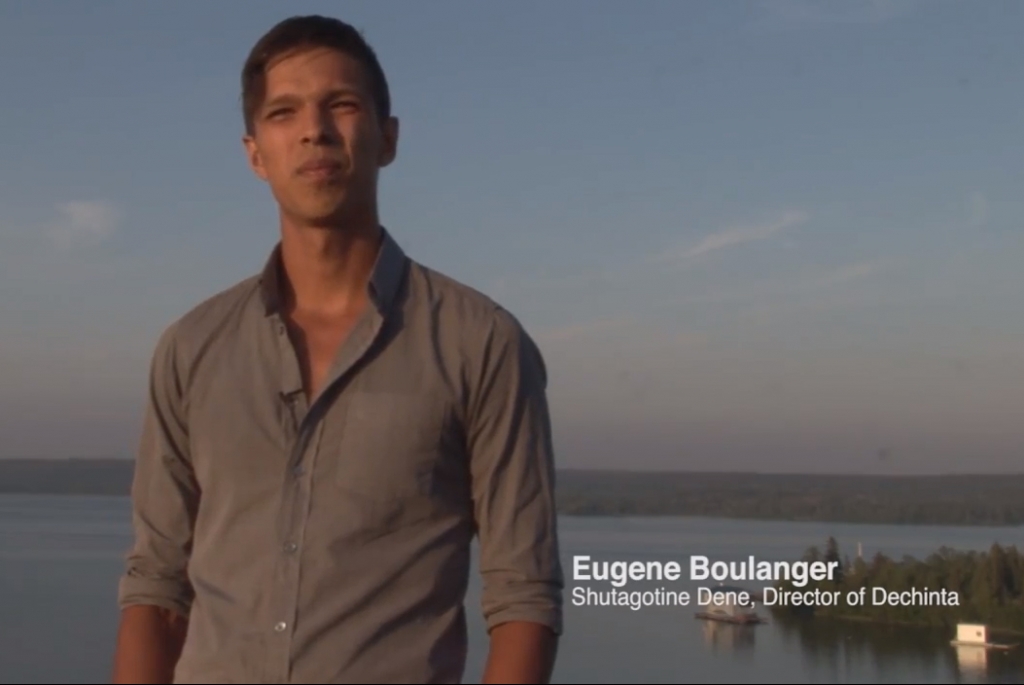

Eugene Boulanger is the current Director of Strategic Partnerships at Dechinta. He is Shutahgotine Dene, born in Tulita in the Northwest Territories, but only recently moved to Yellowknife from Vancouver.

He said accessing core funding and thus finding and keeping permanent staff has always challenged the school. In the past, the Government of the Northwest Territories and Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development funded specific programs, but never provided core funding. That has since changed, and core funding is now a distinct possibility.

Director Stephen Ellis said part of the problem was that Dechinta was not registered as a charity until about a year ago. Today, after successful grant applications from The J.W. McConnell Family Foundation and Tides Canada, Dechinta is able to employ longer-term staff: a two-year contract for Boulanger and money for an in-house program coordinator who works part time. Ellis said the ultimate plan is to have instructors and professors engaged year round.

Ellis said there are many young current young leaders in the north that have participated in Dechinta in the past and continue to contribute. There are also Elders in all the courses - many of whom return each semester.

Kakfwi-Scott said the alumni are the most important elements of Dechinta. She said they continue to dedicate their time and energy to creating a buzz about Dechinta, which lends to the university’s credibility.

“It feels so rewarding, when someone said it changed their life to have that available. There is nothing better than that,” she said. “To have the privilege of getting to know those students and play some small role, it has been one of the greatest experiences of my working life.”

Said Eugene Boulanger: “Dechinta provides a very unique function in the social fabric of the Northwest Territories, it creates youth who are hungry for their culture. It creates people who are willing to go the extra mile to make their life better.”

LESSONS FROM DECHINTA

The Need: A northern, land-based university that would honour the knowledge and culture of Indigenous peoples.

The Project: Dechinta Centre for Research and Learning, Canada’s first northern university.

Challenges: Obtaining core funding needed to keep a permanent staff; legislation that prevented Dechinta from becoming a credit-granting institution.

What Worked: Perseverance: despite some skepticism and early challenges, Dechinta is growing stronger and stronger; constant meetings and relationship building with the upper echelon of governments.

Learnings: Be responsive to the needs of the community -- for example, the land-based component of Dechinta was crucial. Also, alumni can be a source of great strength and support.

Related Tyee stories:

http://thetyee.ca/News/2013/06/27/Aboriginal-Academic-Mentor/

http://thetyee.ca/Series/2011/09/07/Successful-First-Nations-Education/

http://thetyee.ca/Series/2013/06/23/Call-Of-The-Spirit/

Angela Sterritt is a CBC and independent journalist based in Yellowknife. She belongs to the Gitxsan Nation in B.C. This article is one in the series Leading Together insert link, commissioned by The J.W. McConnell Family Foundation of Montreal, that profiles innovative, collaborative experiments in youth empowerment that are delivering concrete results for Aboriginal communities. The stories were produced in collaboration with Journalists for Human Rights and Tyee Solutions Society, and will be co-published by the Aboriginal owned Wawatay Native Communications Society, as well as on the websites of JHR and The Tyee.

An epidemic of addictions has led Mushkegowuk Council in north eastern Ontario to declare a state of emergency.

An epidemic of addictions has led Mushkegowuk Council in north eastern Ontario to declare a state of emergency. A crisis has occurred including issues of...

As we are ready to honour November 11, Remembrance Day I think about the destruction war has done to my James Bay Cree family and my partner Mike’s Irish...